prelúdio, coral e fuga

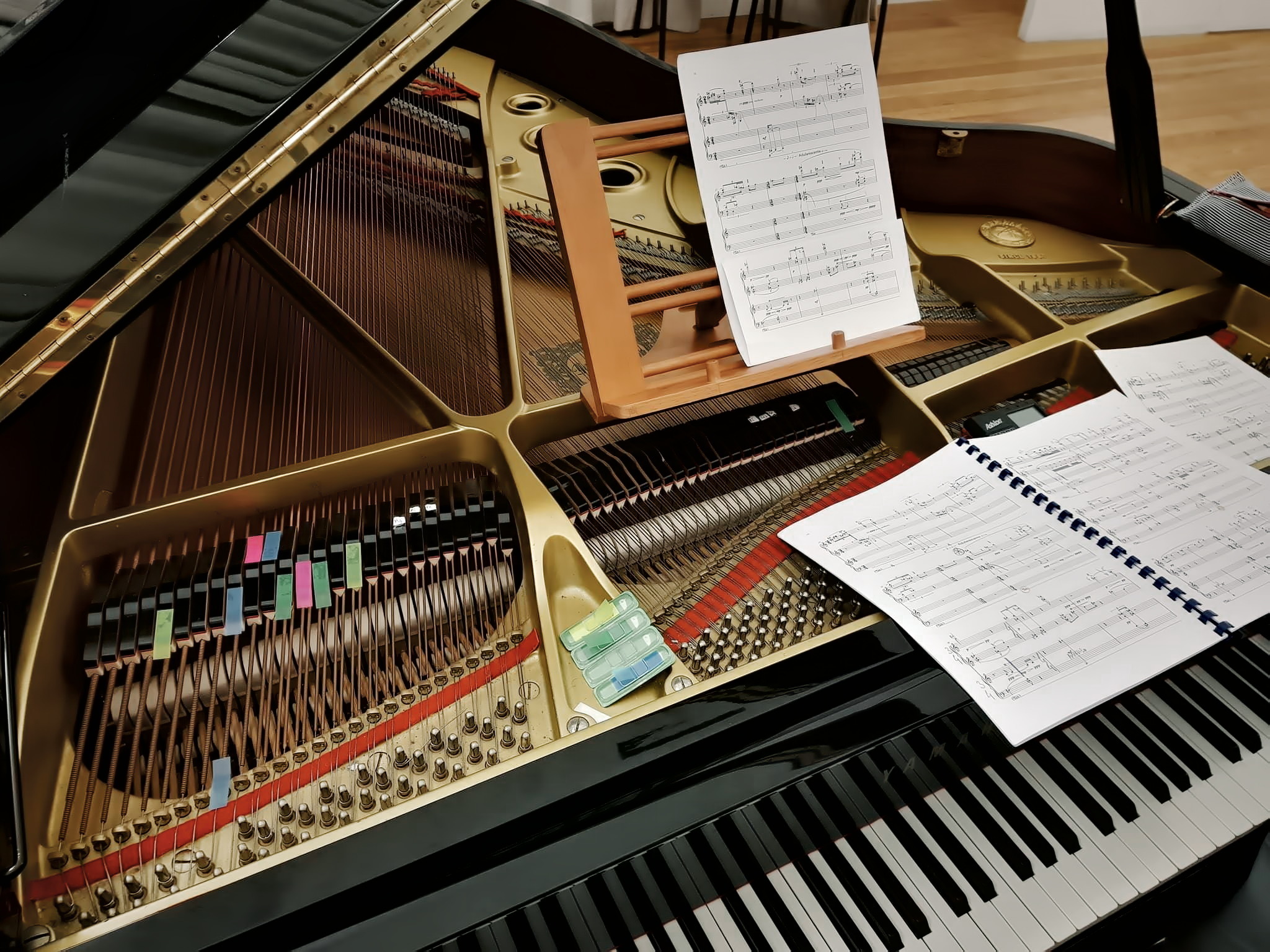

for piano four hands

Premiered March 25, 2018

Escola Superior de Música de Lisboa

Duarte Pereira Martins and Philippe Marques, pf

Chamaram-lhe voz ouviram-na e é muda.

Jorge de Sena, Uma Pequenina Luz

Nenhuma voz me atinge por destino

dela (…)

embora

as ouça claramente, na humihada,

ténue, profunda, vasta e dolorosa,

conquanto doce, humanidade alheia

(…)

Assim se escutam vozes.Jorge de Sena, As Evidências, XIV

How does one listen to voices?

prelúdio, coral e fuga was conceived to be first and foremost about light: shadow, color, reflection. Or rather: about the ways light strikes or shines through a surface.

Almost all of the agogic markings throughout the score refer to properties describing how a material refracts light. Iridescente — iridescent — is the material that changes color depending on the angle at which it is struck by light: a metallic pane shifting its hue as one moves closer, or a labradorite spilling out the light it reflects into a rainbow. In adularescence, on the other hand, light seems to inhabit the inside of a gemstone instead, giving off a warm inner glow. And “caustic”, while more commonly understood as “corrosive” — and the fugue it heads does indeed end up desintegrating —, is also the name of a phenomenon in optics, in which a curved surface bends and concentrates the light it receives. Caustics are those curved bright flourishes that show light emerging transformed after traversing a material. Caustics are light animated by contact, irrevocably changed thereafter.

My chamber music, particularly from the period that follows this piece, usually tends to foreground the interaction between the individual agents in the music making process, thus hindering the formation of a subject-position that can be uncontentiously inhabited by the figure of the composer. This piece, however, is overtly lyrical — though not without some resistance.

I have been asked repeatedly “why a prelude, chorale and fugue”? One of the three might have been palatable in the 21st century, but all together, in order? Highly suspicious. The short answer is: “as a joke”. The longer answer is a bit more convoluted, as one might expect — so much so, in fact, that it is only redeemed when followed by the elegant answer (in the mathematical sense of uniting economy of presentation with depth of potentiality): “as a joke”.

Formal devices tend towards autonomy. Their pushing and pulling — abstracting and reorganizing — of that which they constrain foregrounds its contents’ materiality. In doing so, they productively break apart the meaning conveyed by the syntax of a supposed original message. This happens doubly so with historical forms (though aren’t they all?), loaded with sedimented rhetoric. It is from the resistance exerted against these that subjectivity is affirmed. The speaking voice emerges when it is compelled to fend for itself.

It was through the sonnet — albeit in all its different possible variations on verse grouping — that poet Jorge de Sena composed his large scale cycle As Evidências, which he described as “an anguishingly ripened fruit of a different kind of sincerity; that which we owe to ourselves and to our own expression, in those moments, as if revelations, of transcendental acceptance, too harsh to be remembered every day, even in the presence of poetry, and of objectivity when facing the world, too uncomfortable for the everyday convenience of simply being ourselves”.

We have in the piece two parallel programs of a subjectivity running up against its respective system: one declared — musical material using, rubbing against, perhaps ultimately discarding the forms that gave it shape —, one undeclared — a composer using, rubbing against, perhaps ultimately discarding the structures that gave him shape. A very funny joke — like all jokes explained over paragraphs tend to be.

The two players work to heighten the lyrical undercurrent of the piece. Their relationship is often seemingly adversarial, particularly in the prelude. But this opposition — if attestable at all — dissolves as they shift, resonate, entangle. Henceforth, the players are often called upon to render fragmentary lines — meaning not that the lines are fragmented, but rather that their relationship to the line shifts. In a musically conventional denotation, it is of utmost importance to assure independence, integrity and unity to voices; in one word: subjecthood. This is true even — or especially — when they are tramelled in thick polyphony or in devices such as the hoquetus. Here, we have no “voices” to speak of, but we are hopefully in the presence of something that speaks.

The (at times) intricate physical choreography of the chorale is no display of virtuosity, but in fact a rather physical “filling in” of space left open by the other. In the fugue, the properties that would allow the listener to perceptually differentiate the formal strata are purposefully denied and obscured. Because of this, so do the players — and the listeners — have to negotiate their position against the form: they are the subjects who intentionalize and concede expressive power to the form’s automatisms. More importantly, they also have to face the “voices” which emerge, bent and refracted, from the curved surface of form — and they can only do so obliquely.

“It is as though one has ceased to be the hero or heroine in one’s own story”, writes Elaine Scarry in her essay On Beauty and Being Just. This liquidation of the concept of musical voice (undertaken in a chorale and a fugue!) often feels like “one has just suffered a demotion” (ibid.), so tied that it is to music’s uneasy relationship to speech. “[A]t moments when we believe we are conducting ourselves with equality”, proceeds Scarry, “we are usually instead conducting ourselves as the central figure in our own private story; and when we feel ourselves to be merely adjacent, or lateral (or even subordinate), we are probably more closely approaching a state of equality”.

We cease to be the hero or heroine in one’s own story when alterity strikes — though “not by destiny” — the windowpane through which we peer out into the world, caustics bleeding from the dent imparted. “Most comely / is always [the voice] I meet now, / just because I meet it […]. / And to hear them, I don’t exist”.

Assim se escutam vozes.